White Man Listen! Author Wright, Richard Book condition Used Edition 1st Edition Binding Hardcover Publisher Doubleday & Co. Date published 1957 Bookseller catalogs African American History & Politics. Richard Wright Study Guide (includes following Wright links & more) Richard Wright's White Man, Listen! Richard Wright's Pagan Spain. Cornel West's Evasion of Philosophy, Or, Richard Wright's Revenge. Individual Identity, Historical Meaning, and the Unknown Autodidact 'Bonny Delaney': On Samuel R. White Man, Listen! Wright, Richard on Amazon.com.FREE. shipping on qualifying offers. White Man, Listen!

Catalogue Persistent Identifier

APA Citation

Wright, Richard. (1957). White man, listen. Garden City, N.Y : Doubleday

MLA Citation

Wright, Richard. White man, listen / Richard Wright Doubleday Garden City, N.Y 1957

Australian/Harvard Citation

Wright, Richard. 1957, White man, listen / Richard Wright Doubleday Garden City, N.Y

Wikipedia Citation

| Bib ID | 972518 | |

|---|---|---|

| Format | Book, Online - Google Books | |

| Author |

| |

| Description | Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1957 1 v. |

In the Library

Request this item to view in the Library's reading rooms using your library card. To learn more about how to request items watch this short online video .

| Details | Collect From |

|---|---|

| 325.26 WRI | Main Reading Room - Held offsite |

Order a copy

| Copyright or permission restrictions may apply. We will contact you if necessary. |

| To learn more about Copies Direct watch this short online video . |

by Ralph Dumain

How could one even begin to distinguish black autodidaxy as a concept from the entire history ofblack education in the United States, which of its very nature partakes of the most extremeoutsider status? The first slave who clandestinely taught himself to read when doing so wasagainst the law was the archetypal African-American autodidact. The whole historical strugglefor education in any form in any institutional setting is such a monumental one, why would wewant to set off the black autodidact as a separate subject?

The experience of black education runs the gamut from absolute autodidaxy all the way to blackcolleges and mainstream institutions of higher learning. Even those attaining to permanentacademic posts in this last category were relegated to outsider status until very recently, and, aswe know, American's racial crisis has yet to be definitively solved on any level. There are manyimportant questions in the sociology of knowledge to be examined in all these areas, but given myconcentration on the development of individual capacities by marginalized people, I want toconcentrate my attention on only one slice of this spectrum, from complete autodidaxy up to thelevel of informal group settings and networks, as here we find the aspects of the educationalprocess the hardest to pin down, though the character of the relationship between individualdevelopment and institutional exposure is always an open question under any circumstances. First, leaving aside both mainstream and historically black colleges and universities for themoment, I want to pare down the scope of investigation to the aspects of the subject matter thatinterest me the most. I want to bracket out the educational endeavors of churches, religious cults,and authoritarian political organizations, for while they may indeed thrive outside of officialsociety, there are already plenty of such efforts that are fairly visible and easily ascertainable ineveryday observation: the sort of intrepid folks who sell incense and bean pies and black literatureand Afrocentric bricabrac at subway stops and flea markets are highly visible fixtures; these folkscan look out for themselves. I am interested in less obvious phenomena, and of a more criticaland progressive nature.

I want to reach back historically before I get down to specific individuals. One of the lessresearched aspects of black self-help educational efforts has to do with the development ofinformal and semi-formal intellectual infrastructures, not just colleges and formal schools,but other forms of networking that spread knowledge far and wide beyond formal institutions andseep into the amorphous body of everyday social interaction. Think of reading circles, bookclubs, study groups, the use of YMCA branches or public libraries, lectures, classes,correspondence courses, etc. Who knows what kind of information was spread to whom undersuch circumstances? I am told there is a fascinating history of these phenomena in Harlem alonethat has yet to be written.

Another indispensable part of this story, relating directly to autodidaxy, is the historic importanceof black bibliophiles. Given that mainstream society was dedicated to writing theachievements of peoples of Africa and African descent out of history, black bibliophiles played thecentral role in collecting publications and disseminating information that otherwise never couldhave been circulated or subsequently studied. Probably most readers have heard of ArthurSchomburg, whose pioneering efforts formed the nucleus of the world-renowned SchomburgCenter for Research in Black Culture. You will find three books in my bibliography on the historyof black book collecting, an activity in which, we might add, non-blacks also have participatedprominently.

One could add to this picture by considering key booksellers and bookstores on the otherend of the transaction. This is also a large topic, but of special interest to me is the historic role ofNew York bookseller Walter Goldwater, whose endeavors were succeeded by therecently deceased Bill French, known to me and all serious researchers doing work inBlack Studies.

I'm not going to delve into the historic role of publishers right now, but what waspublished by independent outfits catering to popular education and who read these publicationsare matters of great interest. Here I am not limiting myself to black-oriented publications orpublishers, but to black participation in avenues of popular education as a whole. There is awhole tradition of politicized, generic working class autodidaxy--proletarian education isone name for it-- in which black people participated also. For example, we know that RalphEllison read Haldeman-Julius's famed 'Little Blue Books', but what else do we know ofthe black readership of this sort of material?

I am going to approach the philosophical aspects of the subject through key individuals ofimportance to history and to me personally. I am going to bypass such key well-known blackhistorians and educators as Carter G. Woodson, creator of Negro History Week, whichis now Black History Month, in favor of some other figures of central philosophical interest thatillustrate my approach to the subject.

Hubert Henry Harrison, dubbed the Black Socrates, was the foremost intellectual of theNew Negro Movement, which immediately preceded and partially coincided with the period ofthe Harlem Renaissance. The foremost black intellectual of his time, he succeeded in alienating somany of his erstwhile collaborators that he was all but forgotten only a few years after his death,to be memorialized only by a few such as J.A. Rogers and decades later by JohnJackson. Though he is occasionally cited in passing in historical works as the noted Harlemsoapbox orator, there is hardly ever any detail whatever presented of his life, work, or philosophy. This situation is about to be rectified by the imminent publication of two books, the first volumeof the definitive Harrison biography and a Harrison reader, both by Jeffrey Perry, whichwill restore Harrison to his rightful place in history.

Briefly: Harrison was a consummate autodidact, who made himself knowledgeable in a number ofareas, lectured and wrote on every conceivable subject from the hard sciences to literary criticismto politics. He was insistent on the necessity for black people to have encyclopedic knowledge ofevery conceivable subject matter and to avoid the pitfalls of provincialism, and to use critical,scientific methods of investigation and understanding of the world. Politically, Harrison began asa socialist, but could not abide continuing within the Socialist Party subjected to the pervasivewhite racism within the ranks of labor. Though he coined the slogan 'Race First' and got intorace politics on the ground floor with Marcus Garvey, Harrison ultimately rejected Garvey'sreactionary politics and authoritarianism. Harrison was on the cutting edge of virtually everyprogressive cultural trend from sex education to women's rights. And above all, Harrison was astrident atheist and sworn enemy of the black Church. It is no wonder that recalling his legacywould make a whole lot of black folks very nervous. Harrison is a paradigmatic example of howeasily you can be forgotten after you're gone, no matter how famous you are, if you don'tsucceed in institutionalizing yourself. White people are to blame for attempting to erase a greatdeal of black history, but whites are not the ones responsible for the historical neglect of Harrison(and, I may add, legions of black radicals totally ignored by bourgeois black nationalisthistorians). He is one of the two or three greatest heroes in the struggle for the total freedom ofthe black mind.

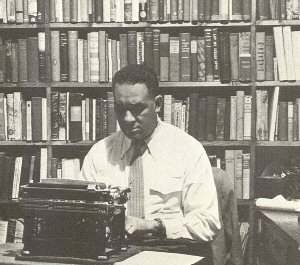

Richard Wright means more to me than just about any other figure. He should becanonized as the greatest and noblest autodidact of our time. Nobody suffered more, traversed agreater social distance, or struggled more fiercely for the right to be an intellectual. There hasnever been a more fanatical devotee of secularism, modernism, individualism, the destruction oftradition, and 'rootless cosmopolitanism' than Richard Wright. Nobody ever fought harderagainst the anti-intellectual, pre-individualistic, religious character of African-American agrariantradition than Richard Wright, who fought his way up from the bowels of human existence--Mississippi--connived and conned his way into borrowing books from the public library whenblack people were not allowed to do this, all the way to the cafes of Paris to hobnob as theintellectual equal of Jean-Paul Sartre. So fierce, so militant, so uncompromising was the nature ofhis intellectual struggle, that it is has not been properly and fully appreciated within the borders ofthe United States to this day, least of all by African-Americans. That Wright has beenmischaracterized and slandered by black intellectuals-- the likes of Margaret Walker,Cornel West, and contemporary academic black feminists-- testifies to how deeply subversive hereally was. You will see much more of my writing on Wright, and then you will learn how muchis at stake in the struggle for the human mind and the role Wright plays in the ideological battle.

Ralph Ellison was college-educated, but he is central to my vision of the autodidact forwhat he had to say about the sociology of knowledge. Ellison's view of the unknown andunofficial transmission of knowledge and cultural influences forms the cornerstone of hisdemocratic vision of American culture. Ellison's generous vision of the unsung greatness thatflows in the veins of the American people shows more love for them than they have ever beencapable of showing for themselves or for one other. Though his novel Invisible Man isoften characterized as a bildungsroman, I want to focus on his nonfiction, which issaturated with his observations about what people--especially black people-- know and what theycan do that you never suspected because American culture at the anonymous grassroots level ismuch richer than official society can know. And so Ralph Ellison told story after story to tell youwhat he witnessed but you didn't know existed: that he grew up in Oklahoma with a group ofNegro boys who used to talk about becoming Renaissance Men. Some people would scoff at thepossibility of such a thing at that place and time among those people, but Ellison testifies that it'sso, and I believe him, because people haven't seen what I've seen and they don't know what Iknow. Ellison related the story of the Negro janitor at the statehouse who became so expert inthe state legal code that legislators consulted him on fine points of law. A black man never had achance to gain either the occupational status or the public recognition to do such work, but thehuman mind is such that it's got to exercise its powers when it has to express itself, to go theextra mile and give everything of itself even when there's no possibility of any recognition, togive one's all and be famous to God alone. And yet therein is the whole creative history of blackAmerica -- to exercise its talents and give everything it's got, to go for broke cause there'snothing to lose. Ellison told the story of the Negro longshoremen who sang opera ... just one of amyriad of examples to show that people nobody knows know things nobody knows they know. Now can I get a witness?

Remember, it's not just black history, it's American history, and it's not just American history, it'sthe human condition, and we in the United States ought to praise our good fortune, how lucky weare to contain within our borders all the peoples of the world, as the ultimate meaning of what itmeans to be human is still punctuated with a question mark. Nobody said it better thanOrnette Coleman about the splendrous variety and magnitude of what has transpiredbeneath the indescribably luscious panorama of these skies: '...If only we .... could be as true ....as the skies of America!'

1 March 2000

©2000 Ralph Dumain

(includes following Wright links & more)

White Man Listen Richard Wright Summary

Home Page | Site Map | What's New | Coming Attractions | Book News

Bibliography | Mini-Bibliographies | Study Guides | Special Sections

My Writings | Other Authors' Texts | Philosophical Quotations

Blogs | Images & Sounds | External Links

CONTACTRalph Dumain

Uploaded 1 March 2000

Man Accept

©2000-2021 Ralph Dumain